The news is starting to circulate in North America, the UK and South Africa. In Canada and the US, we predict that Helium (HE) investment will be the 420 of 2022.

But deeper questions lurk behind the bubble story line. Questions that could deeply affect the future for private company helium producers. What forces will shape international HE markets? Could we see the formation of an OPEC-like cartel for HE? The likely answers lie in the HE industry’s past.

Led Zeppelin and the Power of Siberia

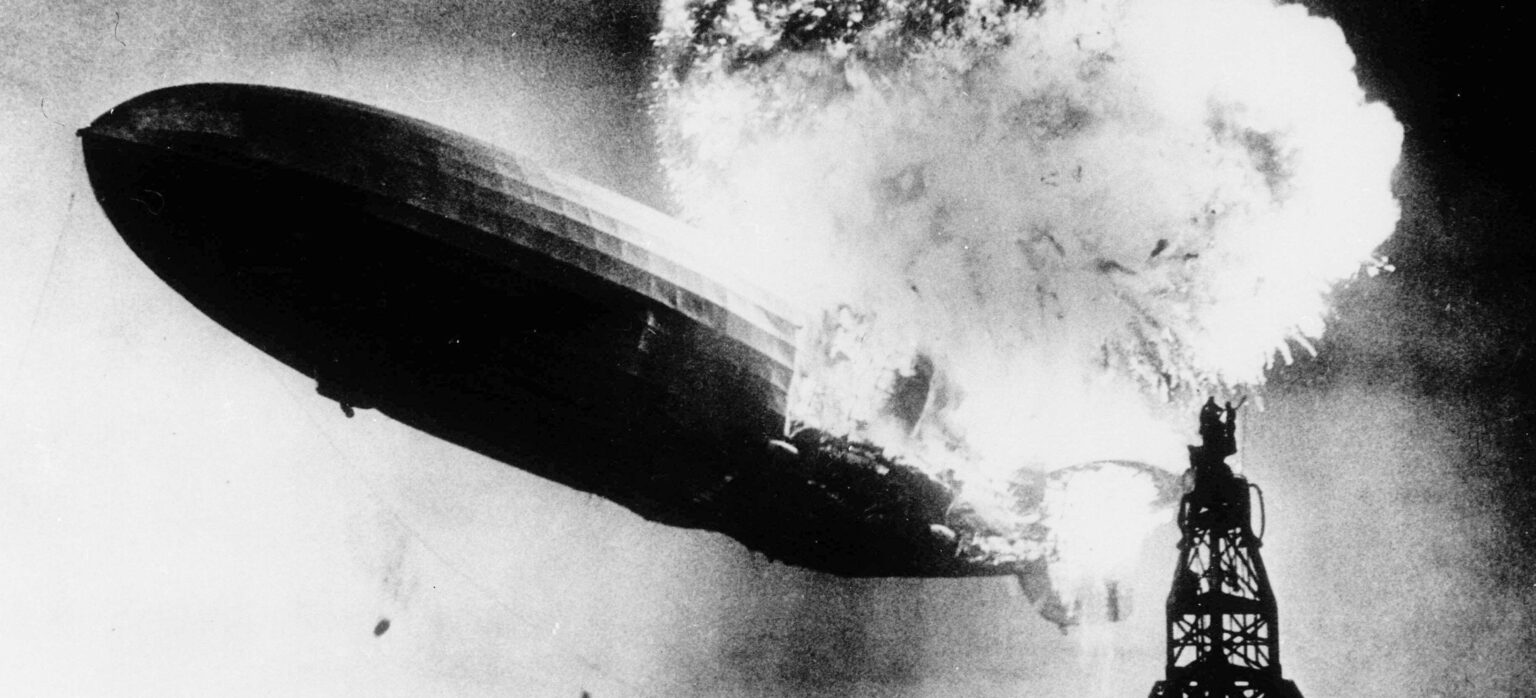

Even fifty-four years before Led Zeppelin I was released, the US Army already knew that Zeppelins were awesome. Helium was preferrable for use in military dirigibles because it was safer than volatile hydrogen lift (ergo, the classic Led Zeppelin I cover depicting the explosion of the Hindenburg).

Following a first discovery in Kansas, the US Army built a HE extraction plant in Texas in 1915 to guarantee its access to the gas. The US produced about 90% of the world’s HE for decades under a Government monopoly.

Like Led Zeppelin’s In Through the Outdoor, the later years of the monopoly where not as good as the early years. The US Government privatized its HE reserves in 1996, which triggered worry of a potential world shortage. A great market need emerged; one that was not met by private investment, but rather by a national oil company (NOC) from Africa.

It is important to understand that HE atoms are most often found in natural gas reservoirs, and because NOCs control the largest natural gas volumes and have access to enormous capital, they have had (and still have) a natural advance in the HE game.

The first to respond to the coming HE shortage was Sonatrach, the Algerian NOC, with the development of the Arzew field. This plant was followed by other large NOC plants at Skikda (Algeria) and Ras Laffan (Qatar).

Algeria and Qatar together now produce about as much HE per year as the US. But new plans are afoot that will tilt market share decidedly in favour of the NOCs.

One of Russia’s NOCs (GazProm) is presently building one of the world’s largest natural gas processing facilities in the Far East ($13B) to feed the Power of Siberia natural gas pipeline. The so-called Amur Project be the world’s largest HE production plant with a capacity of about 60 million m3 per year of HE. It will increase GazProm’s HE production by 13 times, with market share aspirations of 25-30% within the next decade. Exports will leave from Vladivostok. So, Russian production will compete with current market players, while Qatar plans for expanded plants as well.

NOC-NOC, Who’s There?

Amur. Amur who?

New HE finds by private producers in North America, Tanzania and South Africa have been prospective and some will certainly generate great returns. Yet, while those players are smaller and nimbler, they will have a massive disadvantage as compared to the NOCs in terms of natural gas volumes, capital resources and geopolitical clout.

No one will outflank the NOCs. The HE business will be theirs to control in the way their national governments see fit. And they will see the reliance of other countries on their HE volumes as a useful, strategic tool – as Russia now sees the delivery of gas to China via the Power of Siberia pipeline.

Absent regulatory intervention, smaller, private producers will be HE price-takers in a world where NOCs determine production volumes and timing. Turning taps on and off. If NOC countries band together to manipulate these factors, the result would be an OPEC-like cartel. The question is not if…but when.

Remembering the US itself ran an HE monopoly, it is also possible that jurisdictions permitting private HE investment could do an about-face in response to NOC market pressure – by nationalizing existing production, or at least curtailing license grants to private producers.

What does this all mean? It means that a private HE producer in Alberta, Arizona, Tanzania or South Africa can ill afford to ignore the looming NOC shadow when planning its business strategies. These forces may appear surprising five years from now, but the seedlings are clearly taking root now.

*Photo by Rupert Colley. Photo name Hindenburg disaster.